Welcome to our new series, Node Notes, where we’re spotlighting topics from our bi-weekly research piece, The Node Ahead. If you want to read the full piece, you can check out our blog or sign up to receive The Node Ahead straight to your inbox. This edition of Node Notes is an excerpt from Node Ahead 42.

Analyzing the banking crisis

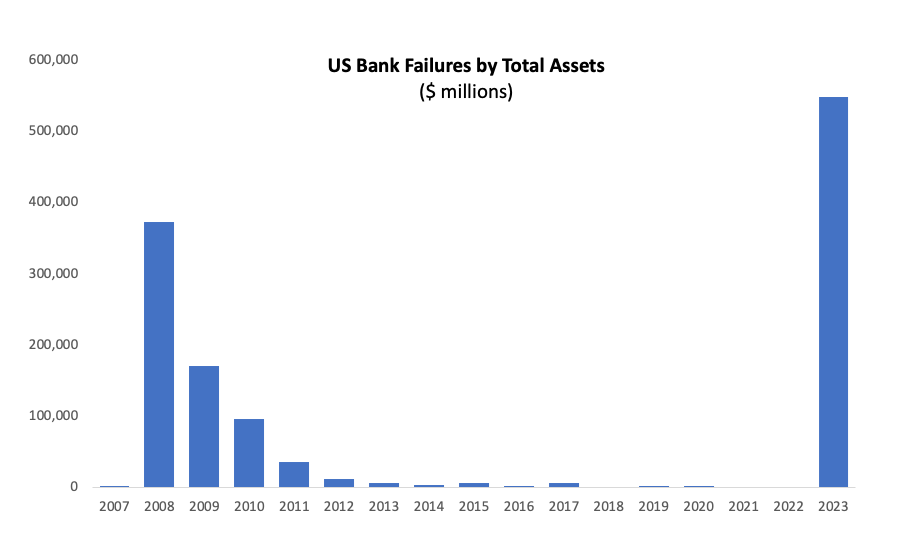

Three of the four largest bank failures in US history occurred in just the last couple of months due primarily to two factors. The first is the Fed’s interest rate policy. From 2008 to 2022, interest rates remained historically low, often near zero. The way banks make most of their money is by taking in deposits, which they pay a small interest rate to customers, and use that money to lend out at a higher rate. That difference in rates they pay depositors vs. the rate they receive through lending is profit for the bank. During the low-interest rate period that lasted 14 years, banks began taking on longer-term duration loans because those paid higher interest rates that would, in turn, make them more money.

Source: https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/bank/

Then COVID hit in March 2020, and soon after, stimulus checks were distributed. People needed a place to put that money, and not surprisingly, bank deposits rose by 35%. Flush with excess cash, banks did what they had been doing for years: they bought long-duration treasuries. These were considered the “safest” assets to purchase, and besides, the Fed had released its public forecasts in 2020 in which it told the market it wouldn’t raise interest rates until after 2023. Sigh…

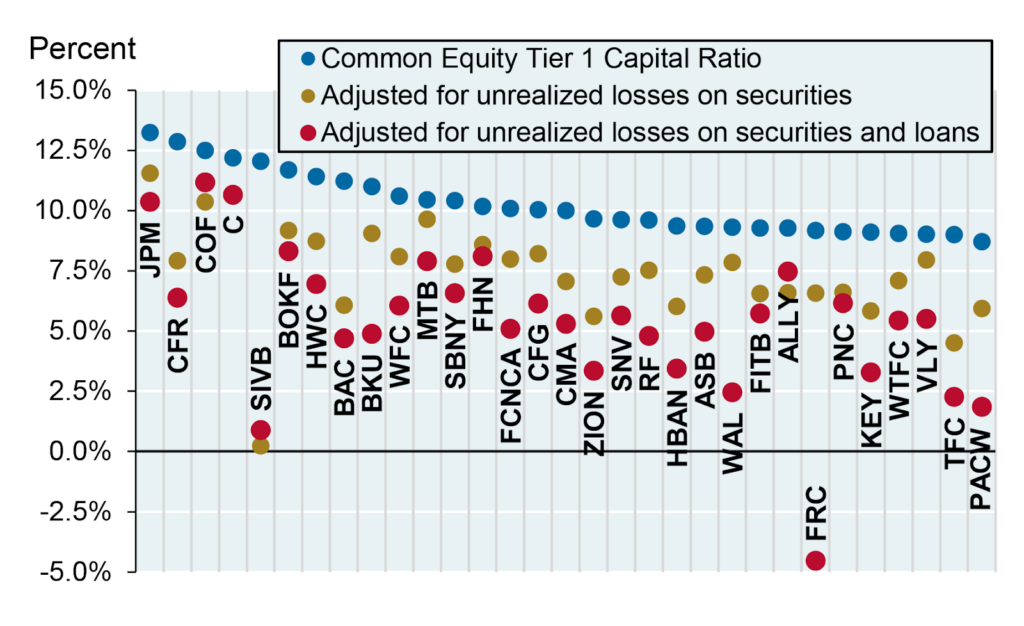

Starting in March 2022, the Fed raised interest rates ten times—so much for those forecasts. This meant that all those long-duration treasuries that banks bought were now worth less than what they paid for them. Many banks (many more than the three that have failed thus far) currently have massive unrealized losses on their balance sheet. In theory, this bank issue could work itself out over time, assuming depositors don’t ask for their money back and allow the bank to hold those assets to maturity. But it will take years, maybe even upwards of a decade, before that maturity happens.

This leads us to the second factor that caused these bank runs: the speed at which communication and bank withdrawals can now take place. People no longer drive to their local bank on a weekday between 9 am – 5 pm, wait in line, and manually initiate a withdrawal. Thanks to 24/7/365 online banking, mobile apps, and APIs, anyone can press a couple of buttons on their phone, and their withdrawal is initiated. And don’t forget about social media, where information now spreads like wildfire, and people can act collectively with much greater efficiency. Remember Gamestop? Now when there is concern over a particular bank’s financial health, that fear can spread faster and further than ever before, and people are able to act on it instantly. Put these two together, and you get $42 million of deposit withdrawals initiated in a single day from Silicon Valley Bank. SVB literally ran out of cash before its management team had time to address the situation. Bankers are not prepared for the speed at which bank runs can happen and are just now coming to grips with that reality.

As much as I would like to be able to tell you these recent bank failures were isolated incidents, there are three reasons why that’s unfortunately not the case. First, according to the Federal Reserve’s own report on the “Impact of Rising Rates on Certain Banks and Supervisory Approach,” released in April, 722 banks reported unrealized losses exceeding 50% of their capital. Even worse, 31 of those banks reported having negative equity levels (yes, that means those banks have liabilities that exceed their assets).

Source: https://privatebank.jpmorgan.com/gl/en/about-us/safety-and-security

Second, banks are losing depositors. Why keep money in low-interest-rate savings accounts that pay on average 0.39% when you can earn 4-5% in money market funds or other investment assets? Yeah, I don’t know either. As a result, bank deposits fell by nearly $720 billion between the second and fourth quarters of 2022, leaving banks’ cash assets at their lowest levels in more than two years. This trend of deposits leaving started well before Silicon Valley Bank or First Republic failed and will continue as long as interest rates remain high. It’s hard to earn money as a bank if you are losing your depositors, especially at the exact same time you are sitting on a bunch of debt that is underwater. As more depositors leave, banks will be forced to realize the losses of those long-duration loans. Even if you believe the banking crisis is over, the reality is many community and regional banks are now simply unprofitable businesses and will likely either go under or be acquired in the coming years.

Third, the value of commercial real estate is falling in large part due to businesses not needing nearly as much office space as more and more employees work remotely. Less demand for office space translates to lower rents which result in lower value for office buildings and building owners less able to make payments on their loans. What does that have to do with banks? I’ll give you one guess as to who lent out the money for a large portion of those commercial real estate buildings. For example, almost 80% of PacWest Bank’s loan book is dedicated to commercial real estate-backed loans and residential mortgages. Numerous other banks have large commercial real estate holdings as well, which means this issue isn’t going away any time soon.

The point I am trying to make is that the banking industry as a whole may be on unstable footing, and that was before Powell raised interest rates again just the other week. This isn’t a crypto-caused problem or a tech startup issue. This is a structural issue for which there is not an easy solution. Yes, there are larger banks that are so well-capitalized that they will be just fine. But all the small and regional banks are currently facing growing pressure on their business models. And should customers start to move their money from smaller to larger banks (because the larger banks are increasingly being viewed as a safer option), that will only further exacerbate the problem and begin concentrating the banking sector.

But isn’t the money in the banks insured by the FDIC? Yes…yes, it is…sort of. FDIC insurance is only good on the first $250,000 in a bank account. Of the $17 trillion of total bank deposits in the US, nearly $7 trillion are not insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. That’s a lot of money sitting in banks that aren’t covered by FDIC. But what about the remaining $10 trillion that is insured? Here is the problem, the FDIC fund is currently only $128.2 billion. With this in mind, the FDIC only has enough money to cover 1.3% of all “insured” deposits within the US. While bank assets wouldn’t go to zero during a bank run, and the FDIC could definitely backstop a few banks, it doesn’t have enough capital to make every depositor at every regional and community bank whole in the event of cascading failures.

Please do not take this argument the wrong way, I’m not saying our banking system is going to collapse. I’m not even arguing that bank failures are likely to accelerate in the near future. All I’m trying to highlight is that the counterparty risk of holding money in a bank, especially community and regional banks, is probably much higher than most people realize, and that risk is growing. It’s likely we will see more banks fail, but it’s also very likely the federal government will step in and backstop the deposits before things get out of hand. But if that were to happen, it would very likely mean that a significant amount of money would need to be printed by the government, which would lead to further currency debasement and likely higher inflation.

If only there was an asset that allowed you to protect your long-term purchasing power while at the same time eliminating your counterparty risk to the traditional financial system.

Bitcoin was created out of the 2008 banking crisis. The stark contrast between bitcoin’s pre-programmed monetary policy, which includes a capped supply and a 50% reduction in new supply issuance every four years, against opaque fiat monetary policies and rate-hike-induced bank failures is becoming more evident by the day. The ability to self-custody bitcoin so as not to have to rely on third-party intermediaries is becoming more valuable. Nasdaq’s BANK index, which includes dozens of US-listed bank stocks, has dropped more than 30% since the start of the year, while bitcoin is up 61% over that same period.

In past issues, we have covered the benefits bitcoin and decentralized finance provide to those living in oppressive regimes or hyperinflationary conditions. It’s why adoption and use of bitcoin as a savings and payment technology is much more prevalent in developing countries, whereas in the West, crypto is still viewed primarily as an investment. However, the US banking crisis is highlighting the value of a financial asset whose monetary policy isn’t controlled by the state, can’t be debased, and can’t be confiscated. As a result, the narrative of bitcoin’s value proposition within the US is slowly beginning to shift from a purely speculative asset to an asset whose properties provide protection against future uncertainty.

Disclaimer: This is not investment advice. The content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice. Nothing contained constitutes a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments in this or in any other jurisdiction in which such solicitation or offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. All Content is information of a general nature and does not address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Opinions expressed are solely that of Brett Munster and do not express the views or opinions of Blockforce Capital or Onramp Invest.