By Brett Munster, Director of Research at Onramp

Welcome back to The Node Ahead, a cryptocurrency and digital asset resource for financial advisors. Every other week, we discuss the latest crypto news and the potential impacts it may have on you and your clients.

In this edition, we’ll cover the following:

- SAB 121

- The acceleration of the US Debt Spiral

What is SAB 121?

On March 31, 2022, the SEC issued Staff Accounting Bulletin Number 121 (aka SAB 121) which describes how the SEC expects entities to account for and disclose any cryptoassets they custody on behalf of customers. Just in case you aren’t intimately familiar with the inner minutia of SEC bureaucracy, a staff accounting bulletin is official public guidance issued by the SEC regarding accounting-related practices. And if you are thinking to yourself right about now, “did he really write an entire newsletter about an obscure accounting notification typically intended for accountants and corporate finance divisions?” The answer to that question is yes, yes, I did. But, I promise, this story is far more interesting than you might initially suspect.

Think of SABs as press releases issued by the SEC on how they expect public companies to handle specific accounting issues. Except SABs are a relatively big deal in the accounting world because 1) they come directly from the agency responsible for regulating public companies and 2) they don’t get issued very often. The SEC typically publishes only 2 or 3 SABs per year on average. So, when the SEC issued their first-ever SAB on the topic of cryptoassets, many companies in the crypto industry or looking to get into the crypto industry took notice.

The issue with SAB 121 is that it heavily discourages banks and custody providers from holding cryptoassets, the reason being the interplay between SAB 121 and capital requirements banks and depository institutions must adhere to. Tier 1 commercial banks typically have a capital requirement of around 5%, meaning for every $100 in assets they hold on their balance sheet, they must also have $5 in cash. This is to help reduce the negative impact of losses from loans or investments and ensure banks have enough capital to honor withdrawals even if those assets decline in value—a good idea for any bank making investments with customer funds.

However, there is a group of banks called Custodian Banks that, rather than take deposits and give out loans, have the primary role of safeguarding the assets of institutional, corporate, or individual clients. This includes holding stock certificates, securities, bonds, precious metals, currencies, and other assets. Custody providers such as BNY Mellon, Northern Trust, and State Street have created massive custodian businesses based on holding financial assets for institutions and charging them a fee. And because they aren’t re-hypothecating those assets like a commercial bank, there is no need for a capital requirement. Thus, the conventional accounting method is to keep those custodied assets off the bank’s balance sheet, which makes sense because those assets belong to the client, not the bank.

The problem with SAB 121 is that it requires all cryptoassets custodied by a bank (or a non-bank that performs custodial services) to recognize the value of those cryptoassets on its own balance sheet regardless of whether it’s a national commercial bank, community bank, credit union, or custodial bank. This triggers the capital requirement on any cryptoassets held for custodial purposes. So even if you wanted to charge a 1% or 2% annual fee to custody cryptoassets, the bank would be required to hold more cash than the fees it could charge. This instantly becomes an unprofitable endeavor. If State Street, which custodies over $15 trillion in customer assets, had to keep 5% of that value in cash on hand at all times, it would not be in business. Basically, SAB 121 makes it economically impossible for banks, including some of the most trusted financial institutions in the world, to custody digital assets at scale.

And that’s the problem: Cryptoassets are being treated differently in the eyes of the SEC than every other asset class, including securities. This is the same SEC that claims all cryptoassets except bitcoin are securities. According to the SEC’s own logic, when consumers purchase cryptoassets, they are securities. Still, apparently, when it comes to storing cryptoassets, the SEC believes they should be accounted for as though they are their own distinct asset class. Which is it? It can’t be both.

And the kicker is that many banks want to custody cryptoassets but haven’t been able to offer that service precisely because of SAB 121. Let’s take BNY, for example. BNY is the world’s largest custodian bank by assets and one of the most trusted custodians in the financial industry. BNY launched a cryptoasset custodian service in 2022, and when they went to register with the NYDFS, they assumed cryptoassets would be treated like every other asset class. When SAB 121 was released by the SEC, BNY sent a letter to the SEC explaining that the guidance issued by the SEC basically makes their crypto business unviable. In the letter, BNY claims, “banks cannot practically serve as qualified custodians for digital assets in any sufficient scale if they are still subject to the threshold limitations of SAB 121.”

This is the most trusted custodian bank in the world. Shouldn’t policymakers and government agencies, who claim crypto is the Wild West and unsafe for consumers, want to encourage proven institutions to bring their expertise to the industry? Wouldn’t that make the industry safer and provide better protections for consumers? Instead, the SEC has issued a directive that effectively eliminates some of the most trusted US financial institutions from offering digital asset custody services.

And that is what is so sinister about SAB 121. The SEC created a rule that makes it impossible for the most trusted banking institutions to enter the crypto industry. Then, it turned around and used the fact that none of the most trusted financial players custody cryptoassets as a reason for the industry being unsafe for consumers. In my opinion, it’s pretty disingenuous to create a problem and then blame the crypto industry for the very problem the SEC created. If the SEC were sincere in its mandate to protect consumers, it would issue guidance encouraging companies with the longest track record of safekeeping assets to enter the space rather than creating rules that purposefully keep them out. It’s this sort of behavior we have seen from the SEC on multiple occasions that leads many to believe Gary Gensler has used his position of authority to further his own political ambitions at the expense of the very same consumers the agency is supposed to protect.

Fortunately, SAB 121 has received a lot of criticism since its publication in March 2022. SEC commissioner Hester Peirce published her own dissent on the day SAB 121 was issued, saying it represented the SEC’s “scattershot and inefficient approach to crypto.” Five senators, including crypto advocate Cynthia Lummis, sent a letter to Gensler in June calling SAB 121 a “backdoor regulation disguised as staff guidance.” Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee Patrick McHenry published a letter in March arguing that SAB 121 puts crypto holders at greater risk than before it was issued. Hal Scott and John Gulliver of Harvard Law School pointed out the absurdity of a rule that would prevent some of the most trusted financial institutions in the world from participating in the crypto economy.

Not only do many disagree with the SEC’s stance, but it also turns out the SEC likely broke the law by issuing SAB 121 in the first place. On October 31, the Government Accountability Office determined that because SAB 121 provides interpretive guidance, the SEC was required by law to submit it for congressional review under the Congressional Review Act (CRA). The SEC never sent SAB 121 to Congress; they just issued it without going through proper rulemaking procedures.

Furthermore, because no formal rule was in place before SAB 121 was issued, the SEC should have worked with the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) – the organization that is typically responsible for setting accounting standards – to determine the accounting rules rather than creating rules on its own. In a Senate hearing in September, Gensler’ testified that the SEC did not confer with prudential regulators or FASB before publishing SAB 121. Instead, FASB added digital assets accounting standards to its agenda in May 2022, after the publication of SAB 121. In other words, the SEC issued SAB 121 without conferring with FASB and arbitrarily created its own accounting guidelines. Either the SEC knew there was no justification for issuing SAB 121 and deliberately chose to do so anyway, or it did so in error (my money is on the former). It’s somewhat ironic that the very organization that has publicly criticized the crypto industry for skirting the rules seems to be doing the very same thing.

So, where do we stand now? After the GAO’s release, certain members of Congress have indicated that they plan to initiate proceedings in Congress in hopes of overturning SAB 121. The optimist in me wants to believe that our elected officials will move forward with repealing SAB 121, but we are talking about Congress here. The other possibility is this now opens the door for BNY (and any other custodian bank) to sue the SEC under the Administrative Procedures Act because the SEC’s failure to follow the rules has caused commercial harm. While it’s unclear exactly what will happen, it’s pretty evident that SAB 121 is yet another example of the SEC unilaterally expanding its authority to start regulating beyond its remit.

The US Debt Spiral Accelerates

Back in June of this year, we dissected the federal government’s 2022 annual budget, explained why the US is now in a debt spiral, and argued the most likely course of action the government would take is to print a lot more money. As a quick recap, the US Government took in $4.9 trillion of tax revenue in 2022 (an all-time record) but spent $6.3 trillion. The largest portion of that spending fell into the Mandatory Expense category, which are expenses the government is required by law to pay. This consists of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, etc. The second category is Discretionary Expenses, which is money formally approved by Congress and the President during each year’s appropriations process. This includes military defense, infrastructure, housing, education, science initiatives, environmental organizations, etc.

Source: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58888

As it has every year since 2001, the US Government ran a budget deficit, meaning it spent more than it collected in taxes. In order to pay for this deficit, the government borrows money to cover the difference. This brings us to our third expense category, Interest Expense. The problem is that every year we run a deficit, we borrow more money, further increasing the interest expense. This drives up total expenses, making it harder to run a balanced budget. To cover that growing deficit, the government borrows more money. This cycle is known as a Debt Spiral, and the US is undoubtedly in one.

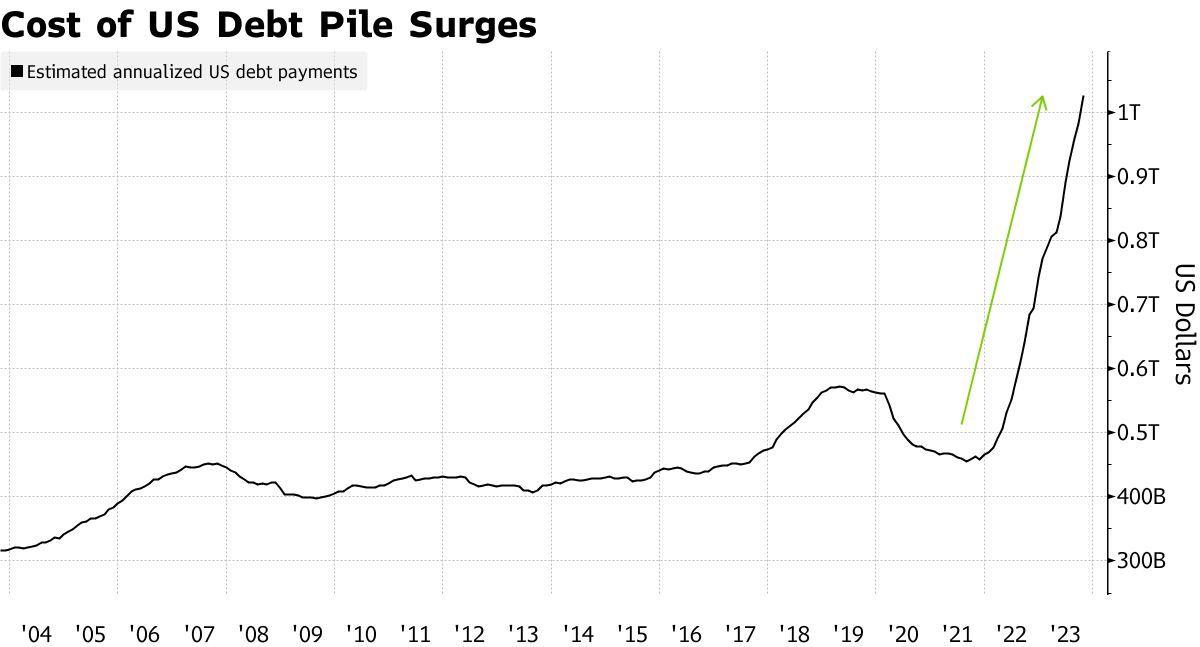

Currently, interest payments on the national debt have become the fastest-growing segment of federal spending. In 2022, the annual interest payment alone was nearly half a trillion dollars. That’s more than the government spent on education, disaster relief, agriculture, science initiatives, space programs, foreign aid, natural resources, and environmental protection combined. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s own projections, interest expense is expected to become the single largest line item on the government’s budget by 2042.

And here is where we pick the story back up because that projection made by the Congressional Budget Office was the best-case scenario. Which brings us to the bad news (believe it or not, the first three paragraphs were the good news): Interest payments on US debt are growing much faster than the projections anticipated.

At the start of 2023, the US total debt was $31.4 trillion. Thanks in part to the debt ceiling being eliminated earlier this year, total debt is now $33.7 trillion (and growing), meaning we have already added $2.3 trillion of debt over the course of this year. To put that in perspective, it took the first 87 years for the US to accumulate the same amount of debt as we just added in 2023 alone. The only other year in history in which the US Government added more debt than this year was in 2020 due to COVID. The difference is in 2020, at least, the debt was used to combat the virus and supplement household incomes. But in 2023, that debt is growing mostly due to the interest payment skyrocketing.

Interest payments on US debt now exceed $1 trillion on an annualized basis. That’s more than double the interest rate payment in 2022. Interest expense is now the second largest line item on the US Government’s budget, behind only Social Security. By 2026, interest payments will likely surpass Social Security and become the largest line item on the budget. According to the government’s own projections, that wasn’t supposed to happen for another 18 years. In fact, mandatory spending plus interest payments now exceeds total tax revenue for the US Government. Even if we cut all discretionary spending to zero, including the military, the US Government would still be running a deficit.

Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-07/us-debt-bill-rockets-past-a-cool-1-trillion-a-year

Unfortunately, interest payments will only keep growing for a few key reasons. First, tax revenue fell from $4.9 trillion in 2022 to $4.4 trillion in 2023 (-9%). At the same time our spending is increasing, our revenue is decreasing. That’s a bad combo. This leads to larger annual deficits, which leads to the need to borrow more. The US borrowed $1.5 trillion in the past 4 months and announced another $1.5 trillion in the next 6 months. At this rate, the debt is on track to grow from $33.7 trillion today to over $50 trillion by the end of the decade. The more we borrow, the larger the interest expense becomes.

Second, not only are we borrowing more, but we are also borrowing at higher interest rates. For the past decade, the government has been able to borrow at near zero percent. Over the last two years, interest rates have risen dramatically meaning any new debt taken on by the US Government is at much higher rates than we previously have been able to borrow. Compounding the problem, $8.2 trillion of US government debt (roughly a quarter of all federal debt) will be maturing in the next 12 months, meaning it will be refinanced at today’s higher rates. Even if we didn’t borrow any more money (which we will), interest expense on the existing debt is set to skyrocket over the next year.

So, we are having to borrow more at higher interest rates, and much of the old debt, which was originally borrowed at near zero, is being refinanced at higher rates. It’s no wonder interest expense is growing so rapidly.

It seems many investors are starting to catch on because the US is having an increasingly harder time finding buyers for its debt. The Treasury’s most recent 30-year bond auction went about as badly as possible. To get enough people to buy, the treasury had to offer a premium over the standard rate. Even then, the primary dealers (those who buy up the leftover supply not taken by investors) had to accept 24.7% of the debt on offer, more than double the 12% average for the past year. To put it in context, this was the worst auction that we have seen since 2011.

Within hours of the auction, yields of the 30-year treasuries spiked by 4.3%. This is the US Treasury Bond, which is supposed to be the most stable, risk-free asset on the planet, trading with more volatility than bitcoin. The reason rates increased so dramatically was because investors are demanding to be compensated for the likelihood that we will have higher perpetual inflation (due to the need to print more money to fund the growing deficits) which makes the return on those bonds worth less over time. The day after the auction, Moody’s downgraded the US credit rating from stable to negative, citing large fiscal deficits and a decline in debt affordability.

Bottom line: The US Government is in a debt spiral, and the demand for US debt is decreasing. We are likely beyond the point where budgetary cuts or raising taxes can fix the issue. The only way the US Government will be able to continue financing its own operations is by turning on the money printer, whether they call it Quantitative Easing or not.

And traditional financial players are beginning to come to the same realization many Bitcoiners came to years ago. US treasuries, especially long-dated ones, are no longer risk-free. Bonds have been crushed this year, and in a higher inflationary environment (as we are likely to have over the next decade due to excessive money printing just to keep the lights on in the government), bonds will very likely return a negative real yield. What happens when Tradfi starts to move some of its bond portfolio into bitcoin?

Bitcoin’s fixed supply, predictable issuance schedule, and the inability for anyone to alter its monetary policy make it the polar opposite of all fiat currencies. Bitcoin is up roughly 120% this year and up over 335% since the start of COVID. It’s why the CEO of Blackrock now refers to bitcoin as “a way to protect yourself from the global debasement of fiat currencies” and its recent run-up in price as “a flight to quality.” Bonds are not the safe store of value they once were, and their returns aren’t keeping up with inflation. With the spot bitcoin ETF likely imminent, thus increasing ease of access, the TradFi world is starting to realize bitcoin can simultaneously help diversify portfolios from a systematic risk perspective and provide real returns that bonds are struggling to achieve.

Bitcoin will not just eat into and expand gold’s $11 trillion market, it will also steal significant market share from the bond market over the next decade.

And the bond market is big. I mean very big. According to the World Economic Forum, the bond market was $133 trillion in 2022. Even if just 1% of that flowed out of bonds and into bitcoin, it would nearly triple bitcoin’s current market size. Given bitcoin’s growing acceptance as a safe haven asset, ability to increase diversification within any portfolio, and historical financial performance, it’s likely bitcoin will steal a lot more than just one percent of the allocation to bonds.

Bitcoin is often referred to as “digital gold,” but the truth is, bitcoin’s store of value narrative extends well beyond just replacing gold. Over the next decade, there will be trillions, if not tens of trillions, of dollars that flow out of other asset classes and into bitcoin. Thinking of bitcoin as just “digital gold” wildly underestimates how big of an impact it’s going to have over the next decade.

In Other News

US Treasuries are spearheading the tokenization boom.

USDC stablecoin issuer Circle is rumored to be considering an IPO in 2024.

HSBC, Europe’s largest bank by total assets, has announced that it will launch a digital asset custody service for institutional clients in 2024.

Microstrategy’s bitcoin holdings now have over $1 billion in unrealized gains.

Crypto supporters submitted more than 120,000 comments arguing against the agency’s DeFi tax proposals.

According to CoinShares, more $1 billion of fresh capital has moved into crypto this year, making 2023 the third-highest year for net inflows on record.

Bitcoin spot ETFs will introduce crypto to a broader investor base.

Disney is launching an NFT marketplace called Disney Pinnacle.

Blackrock filed to launch an Ethereum ETF.

UBS completed the first cross-border repo with a natively issued digital bond fully executed and settled on a public blockchain.

JPMorgan tests tokenized portfolios.

Disclaimer: This is not investment advice. The content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice. Nothing contained constitutes a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments in this or in any other jurisdiction in which such solicitation or offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. All Content is information of a general nature and does not address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Opinions expressed are solely my own and do not express the views or opinions of Blockforce Capital or Onramp Invest.