Welcome back to The Node Ahead, a cryptoasset resource for financial advisors.

Welcome back to The Node Ahead, a cryptoasset resource for financial advisers. Every other week, we discuss the latest crypto news and the potential impacts it may have on you and your clients.

In this edition, we will review:

- Analysis of Past Bear Markets

- Impact of GBTC and Why Grayscale Is Suing the SEC

- SEC Sues Former Coinbase Executives

Before we dive into this week’s newsletter, we quickly wanted to highlight two developments over the past couple of weeks. First, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland recently published a paper entitled “Lightning Network: Turning Bitcoin Into Money.” As we have covered numerous times in past newsletters, the Lightning Network is rapidly growing and making bitcoin an increasingly viable medium of exchange throughout the world. It’s very encouraging to see this progress recognized by Federal Reserve Banks.

Second, Preqin recently ranked Blockforce Capital the number one multi-strategy hedge fund under $250m. Much like the previous awards we have won, we are honored and humbled by the recognition.

On Chain Analysis

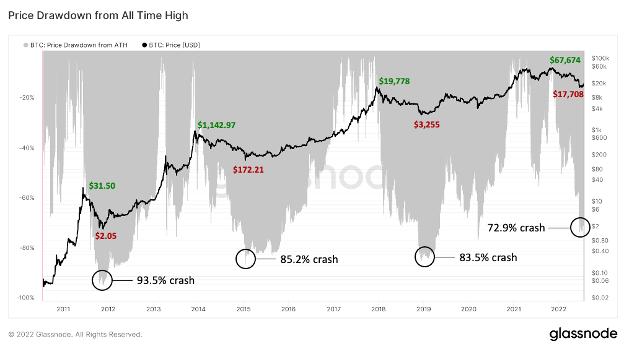

As we can see in the chart below, the drop in price over the first half of the year is the fourth time in bitcoin’s history that the price has fallen 70% or more from its previous all-time high. So, we thought it would be worth analyzing how long these drawdowns have historically taken to reach their bottom, how long they have lasted, and what the recovery has looked like in previous cycles.

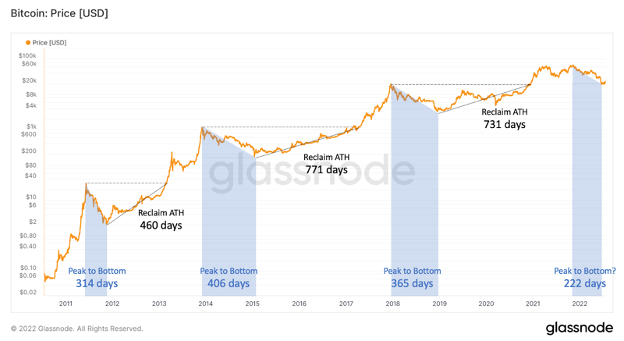

Let’s first examine how long it has historically taken for the price to reach the bottom. Over the past three market cycles, the average time bitcoin took to go from an all-time high to its lowest price for that cycle was 361 days. As of this newsletter’s release, it has been 260 days from bitcoin’s previous all-time high set in November 2022. Thus, history suggests that we may have a few more months before we ultimately bottom out. However, it’s worth highlighting that the time from the peak to the bottom for the 2018 crash was shorter than the 2014 crash suggesting that the drawdown periods may be decreasing as the market continues to mature. If that trend continues, it’s possible that the recent drop to $17,700 could prove to be the bottom of this current cycle, especially considering bitcoin is up nearly 30% since then. If this turns out to be the case, the time from peak to bottom would only be 222 days.

The second piece of the puzzle is analyzing how long it took bitcoin to recover after hitting its floor. It is no surprise that bitcoin has historically taken much longer to recover than it has taken to crash. Across the previous cycles, it took on average 654 days for bitcoin to reclaim its previous all-time high after bottoming out. If we assume the $17,700 is the bottom for this cycle (though we can’t be certain yet), that suggests that bitcoin would reclaim the $67k mark sometime around Q2 or Q3 of 2024.

However, buying opportunities, like those presented when prices crash, do not exist forever, especially in bitcoin. We would argue, given bitcoin’s history of reaching and exceeding its most recent all-time highs, that investing at a 60% or greater drawdown from that all-time high provides attractive return potential (for context, as we write this, we sit at a ~65% drawdown). On the flip side, we have seen bitcoin trade in these deeply discounted ranges for over a year. So, if you were to invest now, how long might you have to endure before prices break out of the 60% drawdown range?

In the previous three cycles, the average number of days bitcoin spent in a 60% drawdown or greater from its previous all-time high is 411. Thus far, bitcoin has been in this range for 44 days. However, as we can see in the graph below, in each subsequent cycle, the time spent in this range has decreased. If that trend continues this cycle, bitcoin may only be in this range for a few months given we first crossed the 60% drawdown threshold in early June. In other words, for those who have dry powder, history would suggest that the next few months will likely prove to be an attractive opportunity to deploy that capital.

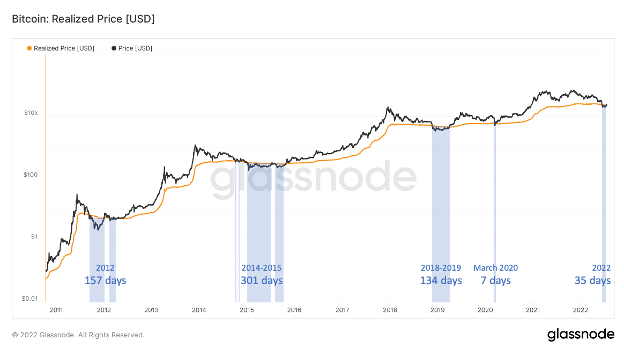

In past issues, we have discussed how bitcoin’s price has only ever crossed below its realized price (the average price each coin was last traded at) five times in its history. Each of the previous four times coincided with the market bottom which is why realized price is one of the most widely recognized on-chain signals. On June 13, 2022, bitcoin’s price dipped below its realized price for only the fifth time in history and stayed there until July 18th. Today, bitcoin’s price sits just above its realized price of $21,900.

How does that compare to previous cycles? If we exclude March 2020 which we can consider an outlier flash event, the average time spent below the Realized Price is 197 days, compared to the current market with 35 days under its realized price thus far.

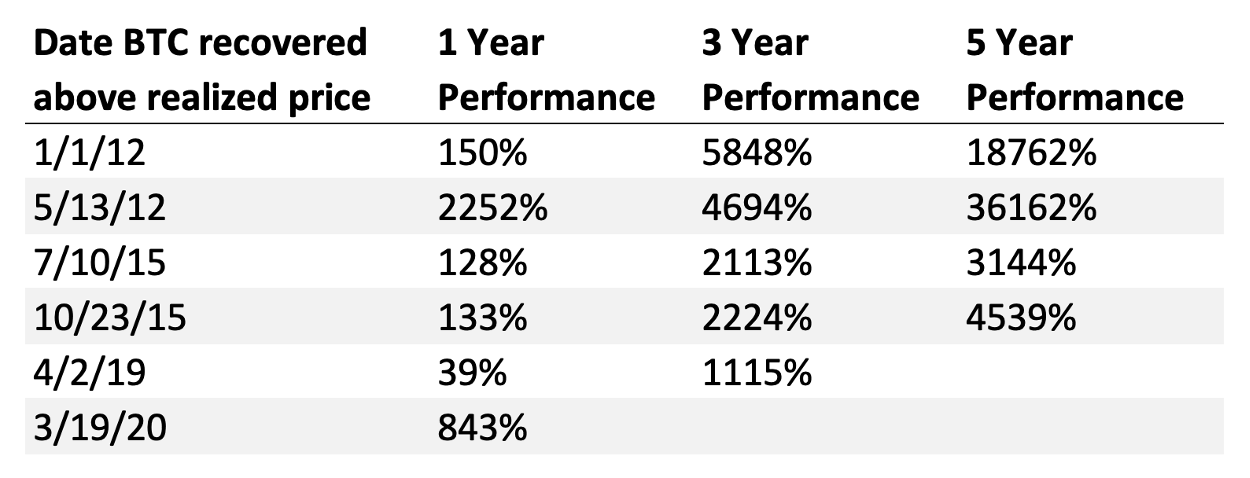

Given we just experienced a period of dipping below the realized price and recovering back above, it’s worth looking at the historical performance had you invested at similar moments in the past. If we isolate the days where bitcoin rallied back above its realized price after being below it (like what happened on July 18th this year), we can see each of those moments in history were extremely lucrative investment opportunities.

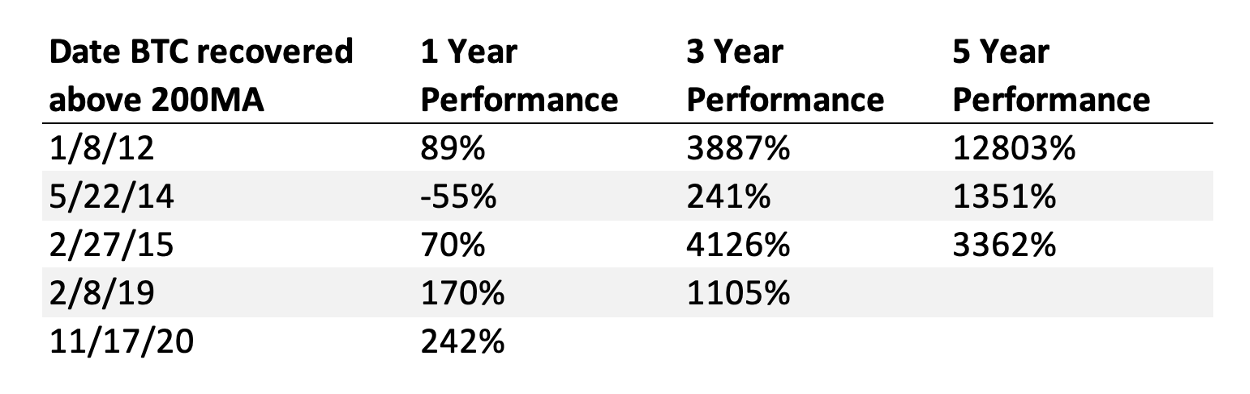

But that’s only one data point. In traditional finance, the 200-day moving average is a widely recognized indicator for determining when to buy or sell. When an asset’s price falls below its 200-day moving average, that is often considered a period of overselling and may indicate an attractive investment opportunity. It turns out, that the 200-day moving average is a pretty decent indicator for bitcoin as well. Bitcoin has traded below its 200-day moving average 5 times prior to 2021 with each coinciding with a market bottom. In November, bitcoin fell below its 200-day moving average for only the 6th time and has remained under that mark ever since.

If we isolate the days where bitcoin rallied back above its 200-day moving average after being below it, we can see each of those moments in history were also very lucrative investment opportunities.

After reviewing the data, it’s likely bitcoin and the crypto markets could remain in a trough for a little while longer. These periods of time do not come along very often and have proven to be incredible investment opportunities in the past. The other lesson this exercise has proven is that you don’t have to perfectly time the bottom to generate outsized returns. You simply need to allocate during times in which crypto is undervalued (like it is today) and remain committed to a long-term time investment horizon.

As always, the on-chain data is provided by Glassnode. If you would like to have access to the data yourself, you can sign up here: Glassnode Sign Up Link

Grayscale sues the SEC

There is a compelling case to be made that no single financial product has had a greater impact on the crypto market than the Grayscale Bitcoin Trust, otherwise known as GBTC. At its peak, GBTC was the largest public holder of bitcoin with over 700,000 BTC worth upwards of $40 billion. Its structure, born out of necessity due to poor regulatory policies, became the original source for much of the yield offered by many of the centralized lending platforms that recently crashed. To understand the rapid growth GBTC experienced, the impact it has had on the industry and why Grayscale is now suing the SEC, we must start at the beginning.

Back in 2013, as bitcoin’s price rose from $13 to over $1,100, interest in BTC was gaining mainstream attention for the first time. While retail investors were able to open Coinbase accounts and start buying, institutions had a great deal of trouble accessing bitcoin. Back then, there wasn’t the institutional infrastructure that exists today, and many large allocators were not able to hold BTC themselves for compliance reasons. What they needed was a way to gain exposure to BTC, without holding the asset directly.

It’s no coincidence that 2013 was also the year that the first bitcoin ETF application was filed by the Winklevoss brothers. A bitcoin ETF is a publicly traded fund that holds bitcoin. The issuing company is responsible for custodying the asset and then sells shares of the ETF on a traditional financial exchange. Packaging bitcoin up as an ETF means organizations such as Schwab or any institution managing 401ks can easily access the asset class. Thus, an ETF would be an easy way for many institutional capital allocators to gain exposure to bitcoin without having to worry about the complexity of holding it themselves. It’s the same way many institutions get exposure to gold and other assets today.

However, the SEC rejected the application and every other spot-based ETF application to this day (we will come back to the SEC later). But just because an ETF was denied didn’t mean demand from the market went away. It was only a matter of time until someone figured out how to service that demand. Enter Grayscale.

Established in 2013 (noticing a pattern?), Grayscale is a subsidiary of Barry Silbert’s Digital Currency Group (DCG). Since launching, Grayscale has grown into the world’s largest digital currency asset manager with fifteen investment products. However, the product they are most well-known for is the Grayscale Bitcoin Trust (GBTC) which first debuted in September 2013.

Because of the SEC’s ruling, GBTC was not structured as an ETF but rather as a public trust which falls under the purview of FINRA. Both trusts and ETFs are pooled investment products with the key differences being costs and how investors buy and sell shares. With an ETF, every time the market buys or sells a share in the ETF, the ETF buys or sells a corresponding amount of the underlying asset (in this case bitcoin). Thus, an ETF closely tracks the price of bitcoin.

In contrast, a trust is structured as a company and is considered a “closed-end fund.” In short, GBTC would open a fund, raise money from accredited investors and use that capital to buy bitcoin. Those investors had to agree to a 6-month lockup period where they couldn’t sell their stake in the trust but once that period expired, were free to trade their position on the open market. However, the number of bitcoin purchased by the trust is fixed. Unlike an ETF that would adjust the supply of the underlying asset as shares were bought and sold, GBTC doesn’t have that flexibility. Thus, if demand for shares increased, so would the price of the shares but not the amount of supply within the trust. As a result, shares of GBTC would then trade at a premium to the actual price of bitcoin (aka “spot price”).

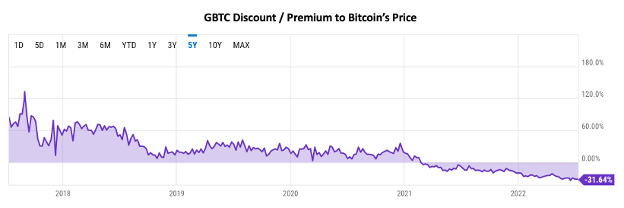

And that is exactly what happened. Despite paying a premium to spot and the higher costs associated with a trust (GBTC charges 2% management fee per year whereas an ETF’s costs are typically nominal), demand for GBTC soared between 2013 – 2020. And so did the premium.

For years, GBTC often traded between 20-50% higher than the spot price of bitcoin simply because GBTC was the only way to “buy” bitcoin within the confines of the traditional financial system. During the mania of 2017, the premium rose to above 100% meaning buying bitcoin through GBTC was twice as expensive as buying bitcoin directly on a crypto exchange. This dislocation in price between GBTC shares and bitcoin’s spot price also meant that sophisticated investors could arbitrage that premium. The SEC’s refusal to approve a bitcoin ETF led to the worst kept secret in crypto which affectionately became known as the “GBTC Trade.”

The GBTC trade works like this. Accredited investors such as hedge funds borrow bitcoin to buy GBTC shares in its initial, private market subscription. Those investors are required to hold onto the shares for a minimum of six months but when the lock-up expires, they can sell the shares on the open market which as we explained, traded at a premium. These investors then use the proceeds to pay back the lender for the borrowed bitcoin and pocket the difference. The beauty of the trade was that it didn’t matter if the price of bitcoin went up or down, so long as GBTC traded at a premium, this strategy was profitable.

However, GBTC’s premium existed because from 2015 to the start of 2021, GBTC was the only bitcoin game in town. However, on February 18, 2021, the world’s first exchange-traded fund backed by physically settled bitcoin called The Purpose Bitcoin ETF (BTCC) started trading on the Toronto Stock Exchange. One month after it hit the market, it amassed $1 billion of assets under management, making it one of the fastest-growing ETFs ever providing further evidence of just how eager investors are for an easy and secure way to get exposure to bitcoin. Since then, more than 70 ETFs or ETPs have been launched throughout the world, though the SEC has yet to approve a spot-based bitcoin ETF in the US.

This meant that institutional investors suddenly had better options than GBTC because these ETFs are cheaper and trade much closer to the spot price of bitcoin. Within weeks of BTCC launching in Canada, flows into GBTC vanished and the premium quickly turned into a discount (ie: GBTC now trades at less than the price of bitcoin). This meant all those who bought GBTC during its private market placement were now losing money and because they were locked up for 6 months, there was nothing they could do about it. The GBTC trade had completely flipped on them.

Source: yCharts

Among those who participated in this strategy were centralized lenders such as Celsius and Blockfi. Want to know where those high yields were originally coming from? A lot of it came from these centralized lenders taking customer deposits and engaging in the GBTC trade. That trade turned negative right around the time Blockfi started cutting its rates and raising more capital (not a coincidence). Celsius, rather than cut rates, decided to pursue even more risky strategies which didn’t go well when the market turned as we covered in Issue 21 of this newsletter. Celsius is now filing for bankruptcy.

But the most aggressive actor was Three Arrows Capital (3AC) who in January of 2021 had a $1.2 billion position in GBTC and held the largest position of any investor. Yes, the same Three Arrows Capital that recently collapsed. Want to know where everything started going wrong for 3AC? Look no further than GBTC’s flip from premium to discount. The firm had borrowed capital from numerous sources and when the GBTC trade flipped on them, they found themselves unable to pay back those loans. In a recent interview with Bloomberg, the founders of 3AC acknowledged that the GBTC trade, along with Terra’s collapse and the de-pegging of stETH, led to the firm’s bankruptcy.

In an interview with Bloomberg, Nic Carter, a partner at Castle Island Ventures, summed it up perfectly. “Basically, too many funds plowed capital into this trade thinking it was a slam dunk, and then as that capital matured and the units in the trust became market-tradable, the demand that they expected to materialize wasn’t there from the market.”

Not trying to absolve 3AC or others of poor risk management, but had the SEC simply approved a spot-based ETF there never would have been the need for the trust structure, and the GBTC trade never would have existed, to begin with. Or had the SEC not rejected GBTC’s request to convert to an ETF last October, GBTC would have likely reduced the discount and traded much closer to the spot price of bitcoin meaning there would have been far fewer losses in the market. Had the SEC acted differently, it’s possible that many of the blowups of the past month or two might have been avoided.

The SEC has denied over a dozen bitcoin spot ETFs in the past year alone, countless others if you go back to 2013, including Grayscale’s second attempt earlier this year to convert GBTC to an ETF structure. Last week the Director of Enforcement at the SEC admitted in a congressional hearing that the SEC has attempted to crack down on crypto companies outside of its jurisdiction. Now Grayscale is suing the SEC, arguing that because so many other ETFs exist and because the SEC has approved four futures-based ETFs and an ETF that shorts bitcoin, the SEC has no good reason for denying their application. Frankly, Grayscale has a compelling case.

More SEC Lawsuits

Last Thursday, the DOJ arrested a former Coinbase executive, his brother, and a friend for insider trading. Ishan Wahi, who worked within the assets listing team at Coinbase, was charged with repeatedly tipping his brother Nikhil Wahi and friend Sameer Ramani about new coins that were soon to be made available to buy and sell on Coinbase. It’s typical for coins to experience a jump in price shortly after being listed on Coinbase because it’s often the first time a much wider portion of the public has access to investing in those coins. Knowing this, the accused would purchase those coins prior to their listing and then profit from the bump in price once the coin went live on Coinbase’s exchange. The three of them made at least $1.5 million across 25 different crypto assets in what US Attorney Damian Williams described as “the first ever insider trading case involving cryptocurrency markets.”

This was an illegal act and kudos to the DOJ for arresting these individuals. But then something else happened: the SEC filed a lawsuit in parallel with the DOJ claiming that at least 9 of the assets traded by Wahi and Ramani were securities.

Why would the SEC jump in on a DOJ case? In short, it’s a backdoor for the agency to increase its authority over the crypto industry without congressional approval. For more than a year, Gensler has been advocating that crypto exchanges and lenders need to register with the SEC. In addition to accusing the three defendants of breaking the law, it’s also accusing ten unrelated, uncharged companies of breaking the law. Nine for failure to register their digital asset as a security and one (Coinbase) for operating an unregistered securities exchange. But as Jake Chervinsky of the Blockchain Association pointed out on Twitter, because the SEC didn’t name the nine companies responsible for those tokens as defendants, they aren’t allowed to defend themselves in court.

Of course, Coinbase refutes the claim that any of the tokens listed on its exchange are securities.

The purpose of this post isn’t to debate which digital assets are securities and which aren’t. Are there assets listed on Coinbase and other exchanges that should be labeled as securities? Most likely. Are there a significant number of assets that are also listed on exchanges that should be classified as something other than a security? Absolutely.

The problem is there have never been clear definitions or guidelines established for categorizing digital assets. Modern securities law was put into place by the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 meaning we are trying to fit cryptoassets into a framework that is almost 100 years old. Simply stated, current securities law is not well-suited to govern digital assets. Thus, Coinbase and other exchanges are operating in an unclear regulatory environment despite wanting and asking regulators for clarity for years. Instead of providing clear rules, Gary Gensler has repeatedly chosen to start with enforcement and create the rules after.

For example, Gary Gensler has made multiple comments over the years about how bitcoin and Ether are not securities. Thus, by his own admission, not all cryptoassets are securities. However, he has also claimed for years that “most” cryptoassets are securities yet never once provided any guidelines, rules, or clarity on how to distinguish between those that are and those that aren’t. Making matters more confusing, the CFTC has publicly stated they believe most cryptoassets are commodities.

Even in this lawsuit, the SEC claims 9 of the assets were securities yet there were at least 25 cryptoassets traded by the perpetrators. What about the other 16 cryptoassets? Why were they not considered securities by the SEC in its lawsuit? How is the SEC determining the difference? Even with regards to the 9 assets listed by the SEC, this is the first time the SEC has ever commented on these specific assets. Why is it that we are learning the SEC’s views on individual cryptoassets for the first time in a federal lawsuit rather than in guidance or rulemaking? Finally, why is it that the DOJ reviewed the same facts and chose not to file securities fraud charges against those involved? The SEC, under Gary Gensler, refuses to provide answers to these questions. Federal agencies aren’t supposed to go around accusing people and companies of breaking the law without explaining their rationale and providing due process.

In Coinbase’s defense, they have publicly and privately asked the SEC directly for this clarity for years and have yet to get anything from the agency. Last year, Coinbase tried to actively engage with the SEC for 6 months about a new product without any response and when Coinbase did announce plans to launch that product, the SEC threatened to sue without providing an explanation. Following this latest lawsuit from the SEC, Coinbase submitted a petition once again asking the agency to develop rules for what the SEC determines to be digital securities. The company is simply asking the SEC to “develop a workable regulatory framework for digital asset securities guided by formal procedures and a public notice-and-comment process, rather than through arbitrary enforcement or guidance developed behind closed doors.”

Even in the most recent Congressional hearing, representatives on both sides of the aisle expressed frustration with the SEC’s tendency to regulate through enforcement without providing any clear guidelines. For years, the SEC could have written rules for crypto, which would allow for public input and an open process. Thus far, the agency has declined to do so.

We don’t want to let alleged insider traders off the hook. They should go to jail if they did what the DOJ claims. At the same time, we believe the SEC is not operating in good faith, and that too should be condemned.

The SEC’s stated mission of protecting investors is a noble one. Unfortunately, under Gary Gensler, the agency has routinely acted contrary to that mission. As CFTC member Caroline Pham wrote in a public statement, “The case SEC v. Wahi is a striking example of ‘regulation by enforcement.’ Regulatory clarity comes from being out in the open, not in the dark.”

In Other News

As demand has peaked on the Texas power grid, bitcoin miners have shut down allowing for the load to go elsewhere where it’s needed most.

How blockchain technology is used to save the environment.

Adam Wright, CEO of Vespene Energy, discussed how they are using bitcoin mining to reduce methane emissions on the What Bitcoin Did Podcast.

BTC mining costs reach 10-month lows as miners use more efficient rigs.

Edward Dowd, former managing director at BlackRock, predicts that Bitcoin will become a better financial instrument than gold, and everyone will have it in their portfolio.

S&P Global has launched a DeFi strategy group with the goal of institutionalizing DeFi.

French banking giant BNP Paribas enters the crypto custody space.

The Texas GOP is aiming to enshrine crypto in the state’s constitution.

The Treasury has sent the White House a framework for international cooperation on crypto as requested by president Joe Biden’s executive order. That framework, however, remains under wraps.

In an interview with Yahoo, Gary Gensler reiterated that “bitcoin is a non-security token” and outlined what to expect from the SEC with regards to crypto regulation.

International standard setters publish guidance on stablecoin regulations.

New York Yankees players and staff are now able to convert their salary into bitcoin.

The Chinese bank run in Henan is a stark reminder of the power and necessity of self-custody.

The credit crunch is not the end of crypto lending.

Tesla sold most of its bitcoin holdings in the second quarter to boost its cash position.